by Sarah Macdonald, Times of Oman

A rare banana found in an oasis in Jebel Bani Jaber near Tiwi has pest-resistant characteristics that could help protect the global banana industry, said a German plant scientist.

Dr Andreas Buerkert, from the University of Kassel in Germany, together with Dr Sulaiman Al Khanjari, his former Omani PhD student and later colleague, discovered the banana, referred to as the Umq Bir banana after the oasis where it grows, in 2003, and has been studying it ever since. The unique banana has now been found to have pest-resistant qualities that make it rare among bananas, a trait that could potentially be shared with other types of bananas, a fruit that is under threat from fungal diseases and beetles worldwide.

The Umq Bir banana could also provide Oman with an opportunity to enhance its contribution to collaborative research in local plant species and exert its authority over its genetic resources, Buerkert explained. Fruits of this variety could also be sold as a special Omani product.

“I think it would be great to have this banana growing and market it as a healthy product that will grow throughout Oman without disease problems. Oman can also license the use of that banana by giving legal rights of Umq Bir plantation and…it is always fully participating in research of this banana,” Buerkert told Times of Oman.

Since 1998 Buerkert and colleagues from Sultan Qaboos University (SQU) and different universities in Germany have been researching about the sustainability of the millennia-old oasis agriculture in Oman. In this context they discovered six ancient varieties of wheat that only grow in Oman and make a valuable addition to the world wheat collection.

Ideal ecosystem

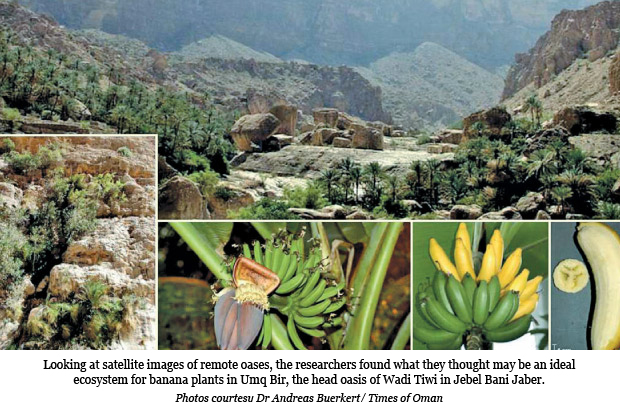

Based on this discovery they decided in 2003 to see if there were also bananas that were unique to Oman. Looking at satellite images of remote oases, he found what he thought may be an ideal ecosystem for banana plants in Umq Bir, the head oasis of Wadi Tiwi in Jebel Bani Jaber.

“It was clear that banana needed a place that was continuously watered…so a very remote oasis would be a great place to look at. More accessible oases are often swamped with new plant materials so we thought we should go to a very remote place with permanent access to water,” he explained. With the help of a Royal Omani Air Force helicopter, Buerkert and Al Khanjari made their way into the wadi.

With binoculars they suddenly discovered the banana plants on a cliff on the rocky wall of the wadi and convinced Khamis Rashid Al Muqaimi, a local farmer, to climb up bare foot and retrieve part of a banana comb. Buerkert later climbed up, too, and got cuttings from the plant.

It is likely that hundreds of years ago the Umq Bir banana had been imported by seafarers to Oman from Southeast Asia, and the same species died out everywhere else. As far as Buerkert knows, it now only grows in Oman.

Back at the University of Kassel Buerkert tried growing the Umq Bir banana. Within two years he had succeeded and the trees were producing fruit.

“We didn’t know whether it was any conventional banana or whether it was a special one. It was pure luck. It was a year and a half later, when we had the identification done, that we realised it was a very interesting find,” he said.

Buerkert asked Belgian scientist Dr Edmond de Langhe, a leading banana expert, to examine the plant and its fruits. As soon as de Langhe saw the first photos he knew it was a rare banana. This banana looked different from others as it was shorter, smaller and finer. There are fewer pieces of fruit on each bunch. Its shelf-life is also shorter so they need to be eaten sooner.

They took one of the bananas from the greenhouse and found that it tasted differently, too. “It smells a bit like apple so it’s a little more fruity,” Buerkert explained.

By 2012 they had results on the banana’s chemistry, and discovered that it produced a so-called “chemical cocktail” that could repel threats to bananas, including fungi and beetles. The banana thus has a powerful antibacterial and antimicrobial group of compounds that are a derivative of tannins, a natural fungi and beetle repellent which is harmless to humans.

Other bananas also have this “chemical cocktail,” Buerkert explained, but it’s not nearly as powerful or fast to develop upon external attack as that of the Omani banana. The beetles, for example, are quickly poisoned when they touch the banana. Their movement slows down and they eventually die.

“We thought that this was fascinating. This could, in fact, provide a tool to protect bananas worldwide, even though we realisedthat the transfer of the underlying genetic properties will not be easy,” he said, adding that triploid edible banana can normally not be simply crossed by sexual mating.

Buerkert said that the Cavendish banana, the most commonly traded variety of bananas, is under attack globally by various fungal diseases and banana beetles. It is at great risk, and as a result of the diseases pressure, has become one of the environmentally dirtiest fruits because of the pesticides it is sprayed with.

Chemical pesticides

In some instances bananas can be sprayed with chemical pesticides up to 42 times before they are picked and sold, but Buerkert said if it were possible to grow bananas with the pest-resistance genes found in the Umq Bir banana, the global banana industry could be greatly helped.

“If the thing really worked it could be a great leap forward in the banana industry by more strongly emphasising biocontrol of organisms. One of the environmentally dirtiest production systems could be dramatically cleaned up using an ancient natural mechanism of banana auto-defense preserved by early Omani seafarers and oasis farmers for many centuries,” said Buerkert.

Source: Times of Oman