Once grown solely for domestic consumption in Southeast Asia, Rambutan is increasingly gaining popularity in western markets. While the demand was initially driven by the growing number of Asian residents in Europe and America, its unusual appearance and sweetness has gained it a niche as an exotic fruit worthy of a global audience. Recent studies indicate that the fruit has antioxidant properties and may be a potential source of an anti-hyperglycemic agent.

Once grown solely for domestic consumption in Southeast Asia, Rambutan is increasingly gaining popularity in western markets. While the demand was initially driven by the growing number of Asian residents in Europe and America, its unusual appearance and sweetness has gained it a niche as an exotic fruit worthy of a global audience. Recent studies indicate that the fruit has antioxidant properties and may be a potential source of an anti-hyperglycemic agent.

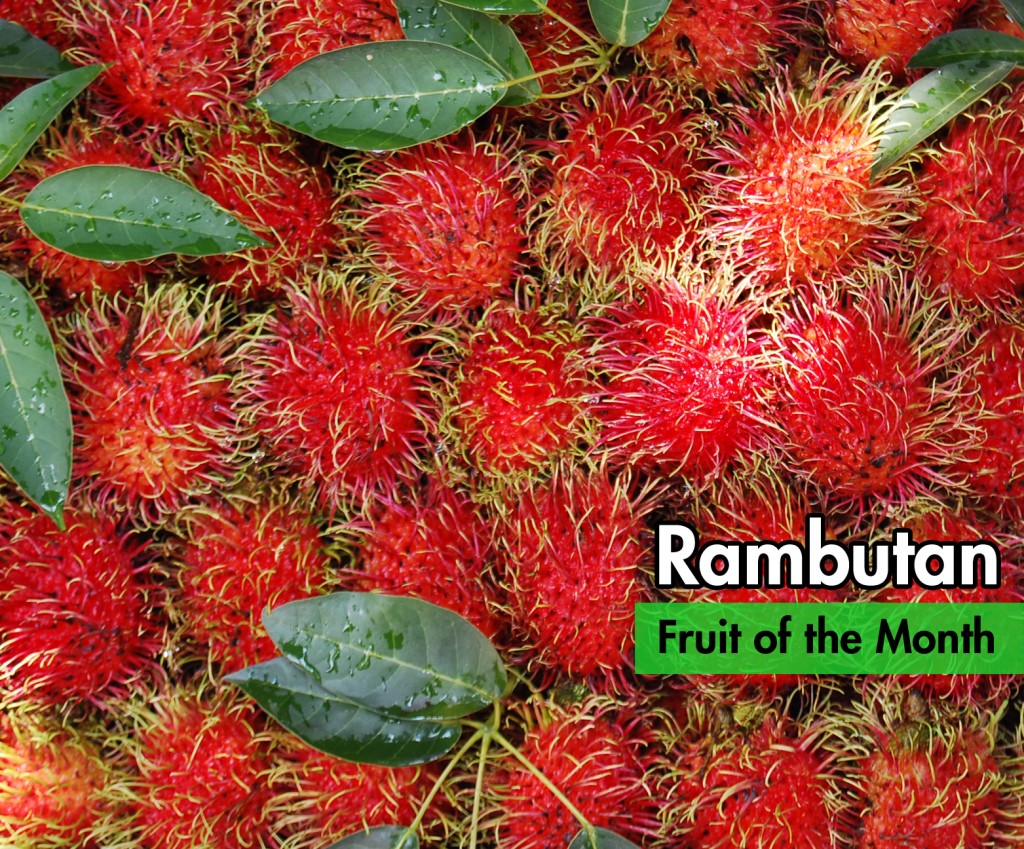

Rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum L.) belongs to the family Sapindaceae and is a close relative of lychee and longan. It derives its name from the Malay word rambut for hair. It is native to the Malaysian archipelago and is widely distributed throughout southern China, the Indo-Chinese region, and the Philippines. Through the Manila Galleon Trade in the 1600s, Spanish botanist Juan de Cuellar sent samples of rambutan to Mexico and it has spread to Hawaii, Colombia, Ecuador, Honduras, Costa Rica, Trinidad, Cuba, and Suriname. Meanwhile, Arab traders introduced it into Zanzibar and it spread to the rest of East Africa. Rambutan was later cultivated in India and South Asia.

Fruit Description

The rambutan is an oval-shaped fruit covered with numerous curved spines or spinterns, giving the fruit a hairy appearance. The thin, leathery fruit skin is either red or yellow when ripe and can be easily peeled away, revealing a white, juicy gelatinous pulp or aril covering a large seed. Depending on the variety, the pulp can be attached to the skin or can be easily separated. The translucent pulp can be sweet to slightly acidic, which is usually eaten as a fresh dessert.

Plant Description

The tree is medium-sized and evergreen with an open structure growing 12-15 m high. They exhibit a strong apical dominance and have a tendency to produce long, upright growth.

Rambutan is a cross-pollinated crop, resulting to a large genetic variation with numerous varieties over generations. Proper selection and vegetative propagation has lead to selected clones that produce desirable fruit characteristics such as thick, firm, flesh that is sweet. Common Malaysian are R134, R156 (yellow variety), R162, R167, R170, R191 and R193 but the current popular variety in Malaysia is R191.The varieties grown in Australia originated from Malaysia such as R9, R134, R156, R162, R167. Varieties Binjai, Rapiah, Garuda, Sibangkok, and Lebak Bulus are popular Indonesian varieties, while the Rongrian, Si Chomphu, and Chanthaburi 1 are the popular varieties in Thailand. The Binjai and Rongrien are also grown in Hawaii. Selected rambutan clones are also grown in Costa Rica, Honduras, and Mexico.

Soil and Climate

Rambutan is suited for the tropics with a moist warm climate with a well-distributed annual rainfall of at least 200 cm. It is intolerant to frost, especially during the juvenile stage. Mature trees may survive a brief period of temperatures as low as 4oC but with severe loss of leaves. The plants can grow at 10-500m above sea level, but should be kept from strong winds as it leads to leaf browning.

The trees grow best in deep, well-drained soils that are rich in organic matter. Soil pH of 4.5-6.5 is suitable for the plant. If it is subjected to soils with a higher pH, the plant experiences iron and zinc deficiencies that induce chlorosis and leaf yellowing.

Propagation

Rambutan is normally propagated vegetatively by bud grafting. For rootstocks, fresh seeds are planted in humus rich medium with good drainage. Seeds germinate within two weeks. When 3-4 leaves sprout, the seedlings are transplanted to polybags with minimum possible damage to roots. Well-grown rootstocks are bud grafted at 8 to 12 months. All leaves must be removed at two weeks after budding. This promotes bud break of the new graft 14 to 17 days later.

Field Establishment

A spacing of 9 m between trees is recommended, but can be modified depending on soil fertility and growth habit of the cultivar. Meanwhile, the tree should ideally have a wide crown with the well-separated branches. The interior should be free from dead, diseased, broken branches, and suckers. Hence, early pruning and training to form an open center is recommended.

In case of drought or long gaps between rainfall, trees may be irrigated either by canals or by drip. Trees should be properly hydrated because the lack of water induces flower drop. Mulching can be done during establishment and dry periods. No mulching should be applied prior to flowering.

Pest Control

For more plant health information, including diagnostic resources, best-practice pest management advice and plant clinic data analysis for targeted crop protection, visit CABI’s Plantwise Knowledge Bank.

Few pests and diseases have been reported by rambutan growers. These include the usual leaf-eating insect (Hypomeces squamosus), leaf-sucking insects (Mictic longicornis, Tessaratoma longicorne), leaf-miners (Phyllocnistic sp.) and mealybugs (Pseudococcus sp). The mango twig-borer (Niphonoclea albata) occasionally appears on rambutan trees. Fruit flies (Bactrocera sp.) attack ripe fruits. Birds and bats also consume and damage the fruits.

There are several pathogens that attack the fruits and cause rotting under warm, moist conditions. Powdery mildew, caused by Oidium sp., may affect the foliage or other parts of the tree. A serious disease, stem canker, caused by Fomes lignosus in the Philippines can be fatal to rambutan trees if not controlled at the outset.

Harvesting

Rambutan requires approximately 107 to 111 days from fruit set to harvest. The best rind appearance and color can be achieved if the fruit is harvested 16 to 28 days after it changes color. The fruits are frequently harvested as early as 10 days after color break to capture the higher market, sacrificing the sweetness and quality of the mature fruit. Fruits harvested 28 days after color break are overripe, having a darker color, lower sugar, and higher acid content.

Average yield is about 2.0 tons per ha during the first 2 years of production to about 8.0 tons per ha after 6 years. Harvesting can be done using a long pole with a cutter or pruner on one end. Damage to the branches while harvesting should be avoided.

Processed Rambutan

Rambutan is also processed to increase added value. Several products like jam, jellies, cocktails, sweets, and canned rambutan are prepared from the pulp. However, much the fresh fruit flavor is lost. The processed fruit is used for pies, ice cream and fruit ice. Sometimes the pulp are canned by stuffing with pineapple in heavy syrup.

Other uses

Timber: The reddish colored rambutan wood is fairly hard, heavy and resistant to insects. However, the small trunks make it too small for timber. However, it is still suitable for construction if carefully dried.

Seeds: The seed kernel yields 37-43% of a solid, white fat resembling cacao butter, with a high level of arachidic acid. The fat is edible and can be used to make soap and candles.

Shoots: Young shoots are used to produce a green color on silk. The fruit dye can also be used as an ingredient to create a black colored dye.

Medicinal uses: In Malaysia, the roots are boiled and used for treating fever. The leaves are effective as poultices to alleviate headache. The bark can be ground as an astringent to treat tongue diseases. The unripe fruit can be used to remove intestinal worms, reduce fever, and relieve diarrhea and dysentery. The dried fruit rind is also sold in Chinese drugstores and for local medicine. Recent scientific investigations suggest that rambutan fruit rind has been shown to be effective in inhibiting enzymes that cause hyperglycemia.

References

- Jalikop, S. H. “Rambutan”. <Retrieved from http://www.fruitipedia.com/Rambutan.htm 2 Feb 2012>

- Mercene, F. Manila Men in the New World: Filipino Migration to Mexico and the Americas from the Sixteenth Century. 2007. The University of the Philippines Press: Diliman, Quezon City

- Morton, J. “Rambutan”. Fruits of Warm Climates. 1987. Miami, FL. <Retrieved from http://www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/rambutan.html>

- Pohlan, J., et. al. “Harvest maturity, harvesting and field handling of rambutan”. Stewart Postharvest Review. April 2008, 2:11.

- Palanisamy, U., et.al. [Asbtract] “Rambutan rind in the management of hyperglycemia”. Food Research International. August 2011. Vol. 44 No. 7

- Palanisamy, U., et.al. [Asbtract] “Rind of the rambutan, Nephelium lappaceum, a potential source of natural antioxidants”. Food Chemistry. July 2008. Vol. 109 No. 1

- Rambutan. Tropical Fruit Net. Issue No. 5.

- Zee, F. “Rambutan and Pili Nuts: Potential Crops for Hawaii”. New Crops. J. Wiley and Sons, Inc. 1993.