by Suthon Sukphisit

Almost 300 years after Westerners introduced the guava to Thailand, the popular ‘farang’ continues to evolve.

Almost 300 years after Westerners introduced the guava to Thailand, the popular ‘farang’ continues to evolve.

When we hear someone mention khanom farang (a muffin-like sweet), man farang (potato), maak farang (chewing gum) and trae farang (natural trumpet), we know that the word farang means the item in question was a Western import into Thai culture. But the word farang itself has two meanings. One is the name of a fruit — the guava — that was introduced by Westerners, and the other refers to Caucasian foreigners.

The guava is considered one of the old Thai fruits, imported into the kingdom as it was during the reign of King Narai almost 300 years ago. It used to be very widespread and popular in Thailand, familiar and loved in every region, and it wasn’t only the fruit that was used. Every part of the plant, the leaves, trunk and bark, and roots all had qualities that made them useful.

Now the original strain of the tree in Thailand is getting lost among the diversifications that have come about through the grafting and cultivation of new ones.

Before turning to the fruit, I’d like to take a look at other parts of the guava tree. Its roots are believed to be effective against nosebleed and the bark yields a dye. The wood of the branches and trunk is extremely tough. Larger pieces can be used to make handles for knives or other tools. Children like to take the Y-shaped joints where branches divide to make slingshots they use to hunt small animals or as a toy.

The leaves of the guava tree have an amazing ability to absorb odours. At the time when ancient historical sites like badly deteriorated stupas were being excavated by Thai government archaeologists to collect their valuable contents before thieves got to them, this property of the leaves proved useful. Some of the ancient stupas had precious antique objects buried underneath them, and the more valuable they were, the deeper the officials would have to dig to reach them.

When descending into the deep, vertical channels leading down to them, they had to deal both with darkness and with a musty and dangerous stink that filled the long-enclosed spaces. The way they dealt with the smell, using a method that was both cheap and efficient, was to cut branches from guava trees and throw them down into the pit first. The leaves would absorb the smell and the officials would follow them down.

If the smell was still strong and the leaves on the first branches had withered, more would be put in until the smell was gone, then the officials would go down and continue their work.

Male heads of households who smoked were often invited to go drinking with their friends. When they returned home drunk, late at night, the best thing to do was to chew some guava leaves to get rid of the smell on their breath. The longer they chewed the leaves, the less odour would remain. These are a few of the uses of the guava’s leaves and branches.

The original form of the guava fruit was favourite in Thailand, but there was a problem with it. It has to be eaten when it is just beginning to ripen, with the skin starting to turn from green to yellow. It took a long time, several weeks, to reach this point. If it was eaten while still green it was bitter, astringent and very hard, but when ripe it was soft and the red pulp inside was sweet.

Another worry was the fact that when it was beginning to ripen it attracted the eye of thieves of many different kinds, bats, birds and squirrels among them.

The way out was to pick them when they were not quite ripe and pickle them. This method has long been used by Chinese pickled fruit vendors. In the past there were many of these vendors. Every community fresh market had pickled fruit for sale — guavas, mangoes, glass apples and more. The fruit were pickled in a solution that included coarse sugar and the dry twigs of a plant called cha-em that coloured them bright yellow.

People who grew the original form of guava did not have to spend much time caring for them, and if they got some ripe fruit to eat before the thieving animals got to them, they considered themselves lucky. The birds were experts at stealing the fruit, and many guava trees grew from the seeds in their droppings. The fruit on these trees was small and astringent, and people referred to them as farang khee nok — “birds**t guavas”.

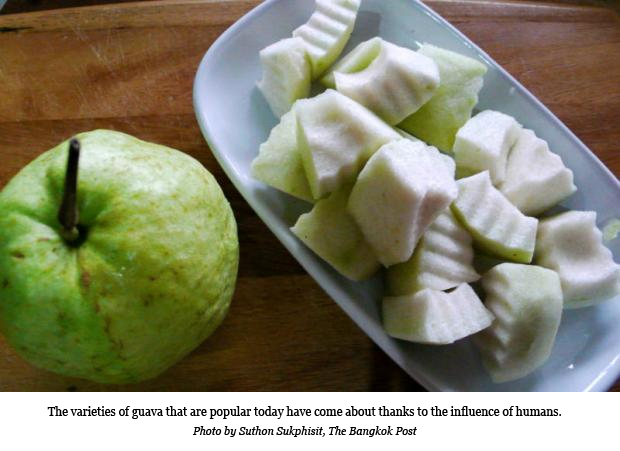

These days there are not many people who like the old guavas and the farang khee nok, and they are generally considered a worthless fruit. New types have appeared to replace them, together with hybrids. Today there is a variety of different kinds of commercially-grown guavas: kimju, Vietnamese, klomsalee, and the seedless paen see thong.

The fruits of these new varieties are very big, the pulp is soft and they either have few seeds or are entirely seedless. But they are also equally bland by nature. Farmers add special fertilisers to make them sweeter.

About 300 years have passed from the time guavas first appeared in Thailand until now, when buyers have a choice of different types unknown to their grandparents. Few of the people buying them at the market today would be interested in the original Thai guava, that for generations was the only choice, but that doesn’t diminish the delicious flavour and aroma that still make it special for those who know.

Source: Bangkok Post