Back to > Major Fruits | Minor Fruits | Underutilized Fruits

![]()

|

||

|

|

||

Names (Common Names):

Avocado, avocatier, aguacate, adpukat, avokad, apukado, avokaa, awokado, bo’, ie dau, apoka (Cook I), pea, avoka, aviota, bata

Synonym:

Persea gratissima Gaertn. (1807), Laurus persia L., Persea drymifolia Schlecht & Cham. (1831), Persea nubigena L.O. Williams (1950), Persea persea (L.) Cockerell

Taxonomy:

The genus Persea is of African-Laurasian origin, with the subgenus Eriodaphne originating in Africa and with the subgenus Persea probably also originating in Africa, entering south-west Laurasia, and then rafting to its present position with tropical North America. Contrary to classification suggestions that identify either the Mexican or the Guatemalan horticultural race as botanically distinct from the other race plus the Lowland (West Indian) jointly, the preponderant evidence favors classifying all three races as equidistant botanical varieties. These three varieties then become Persea americana var. americana Lowland (“West Indian”), var. drymifolia (Mexican) and var. guatemalensis (Guatemalan). The Lowland (West Indian) variety appears to be the most distinct of these three races. Persea nubigena, steyemarkii and floccosa appear to merit ranking as further varieties. Variety nubigena probably is ancestral to var. guatemalensis. Persea schiedeana, however, does appear to merit separate species standing (Scora, Rainer. W. and Bergh, B., 1990).

General Botany:

Tree: The avocado is a dense polymorphic broad-leaved aromatic evergreen tree species of the genus Persea classified in the division Magnoliophyta, class Magnoliopsida, order Magnoliales of the flowering plant family Lauraceae (Myrtle). Camphor (C. camphora), cinnamon (Cinnamomum zeylanicum), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), European bay (Laurus nobilis), and California bay or Oregon myrtle (Umbellularia californica) and laurels are related species.

It is fast growing plant and reaching a height of 20 m with age whilst grafted trees are usually 8-10 m tall, although usually less, and generally have a low branched trunk and an irregular. Some cultivars are columnar, others selected for nearly prostrate form. It makes a good espalier plant for certain cultivar.

Vegetative growth is cyclical with pronounced growth flushes. The avocado sheds many leaves in early spring. There may be one to six shoot flushes per year (Thorp, 1992). Growth is in frequent flushes during warm weather in warmer regions with only one long flush per year in cooler areas. Axillary branching may be proleptic, that is, a shoot develops only after a period of dormancy as a resting bud or sylleptic, where shoot growth occurs simultaneously with the parent axis with no dormant phase (Hall et al., 1978). In avocados, it is quite easy to discern between these two types of axillary branching.

The trees are shallow rooted and have poor water uptake and hydraulic conductance. Roots are coarse and greedy and will raise pavement with age. Injury to branches causes a secretion of dulcitol, a white, powdery sugar, at scars.

Foliage: Avocado leaves are alternate, glossy, elliptic to obovate-oblong, 10–30 cm long, 4–10 cm wide, leathery, upper surface dark green, lower surface glaucous and sparsely hairy; secondary veins prominent, reticulum coarsely areolate; petiole 2–7 cm long. They normally remain on the tree for 2 to 3 years. The leaves of West Indian varieties are scentless, while Guatemalan types are rarely anise-scented and have medicinal use. The leaves of Mexican types have a pronounced anise scent when crushed. The leaves are high in oils and slow to compost and may collect in mounds beneath trees.

Flowers: Although the trees produce an abundance of flowers, usually less than 0.1% of the flowers set fruit and most of these fruits abscise within 6 weeks from full bloom (Whiley and Schaffer, 1994). Avocado flowers are inconspicuous and appear in terminal panicles of 200 – 300 small yellow-green blooms. Each panicle will produce only one to three fruits. Calyx is not persistent in fruit. The flowers (6–7 mm long) are perfect, can be protogynous, meaning the stigma is receptive before the pollen is shed, and protandrous, meaning the pollen is shed before the stigma is receptive, in the same individual. The flowers are either receptive to pollen in the morning or shed pollen in the following afternoon (type A), or are receptive to pollen in the afternoon, and shed pollen in the following morning (type B). This way, self-pollination (of the same flower) is avoided. However, flowers on an entire tree are in different stages, and self-pollination does occur occasionally, but the young fruits fall from the tree prematurely, alluding to a possible post-zygotic self-incompatible mechanism. Pollination of the flowers is mainly by bees. About 5% of flowers are defective in form and sterile. Production is best with cross-pollination between types A and B. The flowers attract bees and hoverflies and pollination usually good except during cool weather. Off-season blooms may appear during the year and often set fruit. Some cultivars bloom and set fruit in alternate years (Boyle, 1980).

| Variety | Type | Variety | Type |

| Alboyce | A | Anaheim | A |

| Arturo | A | Bacon | A |

| Benik | A | Carlsbad | A |

| Clifton | A | Colinson | A |

| Decem | A | Dickinson | A |

| Edranol | B | Elsie | B |

| Emerald | A | Ettinger | B |

| Fuerte | B | Ganter | B |

| Gehee | A | Hass | A |

| Irving | B | Jalna | A |

| Janboyce | A | Jim | B |

| Linda | B | Lula | A |

| Lyon | B | MacArthur | A |

| Marshelline | B | Mayapan | A |

| Mayo (Covacado) | A | Mexicola | A |

| Nabal | B | Northrup | B |

| Nowels | A | Pinkerton | A |

| Puebla | A | Queen | B |

| Regina | B | Rincon | A |

| Reed | A | Ryan | B |

| Santana | B | Sharpless | A |

| Spinks | A | Stewart | A |

| Suke | A | Topa Topa | A |

| Wright | B | Yama | A |

| Zutano | B |

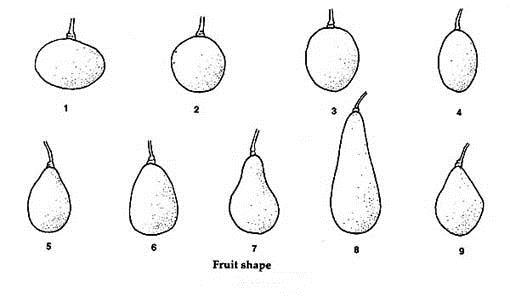

Fruits: The fruit is called butter pear or alligator pear and in Spanish (aguacate). Grafted plants normally produce fruit within one to two years compared to 8 – 20 years for seedlings. Fruits are 7-20 cm long and 7-10 cm in diameter weighs between 100 and 1000 grams, and has a large central seed, 5–6.4 centimeters long (Dowling and Morton, Julia Frances, 1987). It is considered by many to be a drupe, but is botanically classified as a berry (Armstrong, 2000). Sometimes they are 5–7 cm long at end of season or on some naturalized plants. The avocado comes in a variety of shapes, some of which are depicted here:

1. Oblate, 2. Spheriod, 3. High spheroid, 4. Ellipsoid, 5. Narrowly obovate, 6. Obovate, 7. Pyriform, 8. Clavate, 9. Rhomboidal

They may be round, bottle necked, pear-shaped or globose, green or may be tinged with purple usually dark green; pulp fleshy and oily; seed globose, 30–40 mm diameter. The avocado comes in a variety of colors. As the avocado matures, the color will often change in a way characteristic of that variety. Other varieties remain the same color when immature or mature. Below are some typical colors found in avocado.

West Indian type avocados produce enormous, smooth round, glossy green fruits that are low in oil and weigh up to 0.9 kg. Guatemalan types produce medium ovoid or pear-shaped, pebbled green fruits that turn blackish-green when ripe. The fruit of Mexican varieties are small (170 – 283.5 g) with paper-thin skins that turn glossy green or black when ripe. The flesh of avocados is creamy, deep green near the skin, becoming yellowish nearer the single large, inedible ovoid seed with an unusually high amount of fat that is primarily monounsaturated. They also contain a high concentration of dietary fiber, vitamins and potassium. The flesh is hard when harvested but softens to a buttery texture when ripe. Seeds may sprout within an avocado when it is over-matured, causing internal molds and breakdown. Fruit of the cultivated species vary greatly in size, shape, color, texture and flavor. When ripe the flesh should have the consistency of soft butter. The fruit is unique in that it will not ripen until harvested and may be left on the tree for some time (depending on variety) after reaching maturity.

High in mono-saturates, the oil content of avocados is second only to olives among fruits, and sometimes greater. Avocados contain from 5 to 40% oil, the percentage varying with the variety, growing area and seasonal conditions. Only ripe olives have higher oil content. The oil in avocados is 82% mono-unsaturated and 92% of this is oleic acid, as in olive oil. This is the “good oil” important in keeping down cholesterol levels. The rest of the oil content is 8% poly-unsaturated and 10% saturated. Avocados are cholesterol free. Avocados are “nutrient dense”, containing 25 essential nutrients, vitamins & minerals including protein, fibre, vitamins A, B6, C and E as well as essential trace elements of copper, potassium and pantothenic acid. Avocados are also nutrient boosters which enable our bodies to more readily absorb fat-soluble nutrients in foods eaten with the fruit. Avocados contain 2–10 times more protein than most other fruits and vegetables, and this protein contains all of the amino acids essential for humans. Unlike most plants sources it is complete, like egg protein, therefore a very important food for vegetarians. They contain very little sugar, so are ideal for diabetics. They are high in fiber – important for lowering the risk of heart disease, cancer, hypertension and obesity. An excellent baby food, as avocados are smooth, palatable and nutritious. Babies at weaning seldom refuse them and grow to be avocado lovers. For the calorie conscious, there are about 140 calories (670 kilojoules) per serve (half an average size avocado). However experiments have shown that an avocado a day added to a low calorie diet actually assists weight loss. This is probably due to the feeling of “fullness”, thereby decreasing hunger and possibly increasing the metabolic rate. The therapeutic value of avocado oil is related to its fatty acid composition.

Clinical feeding studies in humans have shown that avocado oil can reduce blood cholesterol. The pit, seed, leaves, bark and in some cases fruit can be toxic to some animals, particularly birds, and also humans; the toxicity of the fruit may be an adaptation that assisted seed dispersal by Pleistocene megafauna (mammals, birds and reptiles — that lived on Earth during the Pleistocene epoch and went extinct in a Quaternary extinction event). The ground-up seed mixed with cheese is used as rat and mouse killer.

Reference:

- Adame, E.L. 1994. Plagas del aguacate y su control. IV Curso de Aprobación Fitosanitaria en Aguacate. Facultad de Agrobiología. U. M. S. N. H. Uruapan, Michoacán, México.

- Armstrong, WP (2000). “Fruits Of The Rose, Olive, Avocado & Mahagany Families – Laurel Family: Lauraceae Extract from: http://waynesword.palomar.edu/ecoph17.htm#avocado

- “Avocados, raw, California”. NutritionData.com (2007). Retrieved on 2007-12-29

- Bailey, B.J., and P.M. Hoffman. 1980. Amorbia: ACalifornia avocado insect pest. Department of Entomology,University ofCalifornia, División of Agricultural Sciences. Leaflet 21256Riverside, Ca.U.S.A.

- Boyle, E.M. (1980). Vascular anatomy of the flower, seed, and fruit of Lindera benzoin. Bull. Torreya Bot. Club. 107:409-417.

- Bravo, M.H., et al., 1988. Plagas de frutas. Centro de Entomología y Acaralogía , Colegio de Posgraduados. Montecillo, México pp 49-236

- Bruno Razeto, Jose Longueira, and Thomas Fichet. (1992). Proc. ofSecond World Avocado Congress 1992 pp. 273-279

- California Avocado Comission (2007). Avocado.org. Retrieved March 1, 2007, Web site: http://www.avocado.org/

- Davenport, T.L. Avocado Flowering, Hort. Reviews 8: 257-289.

- Dowling, Curtis F.; Morton, Julia Frances (1987). Fruits of warm climates. Miami, Fla: J.F. Morton.

- “FATTY ALCOHOLS: Unsaturated alcohols”. CyberlipidCenter. Retrieved on 2007-12-29.

- Hirokazu Kawagishi, Yuko Fukumoto, Mina Hatakeyama, Puming He, Hirokazu Arimoto, Takaho Matsuzawa, Yasushi Arimoto, Hiroyuki Suganuma, Takahiro Inakuma, and Kimio Sugiyama. (2001). Liver Injury Suppressing Compounds from Avocado (Persea americana). J. Agric. Food Chem., 49 (5), 2215 -2221, 2001. 10.1021/jf0015120 S0021-8561(00)01512-0

- Koch, F.D. (1983). Avocado Grower’s Handbook, Bonsall Publications,

- López, E. 1990. Manejo de plagas de palta. In the international course: “Producción, Postcosecha y Comercialización de Paltas”. Facultad de Agronomía. Universidad Católica de Valparaíso. Viña del Mar, Chile.

- López-López, L., and Cajuste-Bontemps, J.F. 1999. Efecto del envase de carton corrugado y embalaje en la conservación de la calidad de fruta de aguacate CV. Hass. Revista Chapingo Serie Horticultura 5 Núm. Especial: 359-364.

- Martínez, B.R., and Adame, E.L. 1987. El minador de la hojadel aguacatero, dinámica de población, biología y control. Revista: Fruticultura de Michoacán. Año II, (I), 11pp. 5-26.Uruapan Michoacán.

- Minas K. Papademetriou (2000). Avocado Production in Asia and the Pacific. FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS

- REGIONAL OFFICE FOR ASIA AND THE PACIFIC

- BANGKOK,THAILAND, JULY 2000

- Naveh E, Werman MJ, Sabo E, Neeman I (2002). “Defatted avocado pulp reduces body weight and total hepatic fat but increases plasma cholesterol in male rats fed diets with cholesterol”. J. Nutr. 132 (7): 2015–8.

- Ohr, H. D. , M. D. Coffer, and R. T. McMillan, Jr. (2003) Diseases of Avocado (Persea americana Miller). http://www.apsnet.org/online/common/names/avocado.asp

- Ojewole JA, Amabeoku GJ. (2006). Anticonvulsant effect of Persea americana Mill (Lauraceae) (Avocado) leaf aqueous extract in mice. Phytother Res, 20(8): 696-700.

- SAGAR Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería y Desarrollo Rural. 1999. Revista “Claridades Agropecuarias”, No. 65 “El Aguacate”. Enero de 1999.

- Sánchez-Pérez, J. 2001. Aguacate en postcosecha. Boletín informativo de la APROAM El Aguacatero No. 5, http://www.aproam.com/aguacater5.htm SARH-DGSV. 1981. Lista de insectos y ácaros perjudiciales a los cultivos de México. 2a. Ed. Secretaría de Agricultura y Recursos Hidráulicos – Dirección General de Sanidad Vegetal. Fitófilo, No. 86: 1-196.

- Scora, Rainer. W. and Bergh, B. (1990). THE ORIGINS AND TAXONOMY OF AVOCADO (PERSEA AMERICANA) MILL. LAURACEAE. Acta Hort. (ISHS) 275:387-394

- Thorp, T.G. (1992). A study of modular growth in avocado (Persea americana Mill.) PhD.Dissertation. The University ofAdelaide,South Australia.

- Whiley, A.W. and B. Schaffer. (1994). Avocado, p. 3–35. In: B. Schaffer and P.C. Andersen (eds.). Environmental physiology of fruit crops. vol. 2. Sub-tropical and tropical crops. CRC Press Inc.,Boca Raton,Fla.

- Wikipedia, (2007). Avocado. Retrieved March 5, 2007, from Wikipedia Web site: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avocado

- Yahia, E.M. 2001. Manejo postcosechadel aguacate, In: Memoria del 1er. Congreso Mexicano y Latinoamericanodel Aguacate.Uruapan, Michoacán, México. Octubre 2001.

- Yahia, E. 2003. Manejo postcosechadel aguacate, 2ª. Parte. Boletín informativo de APROAM El Aguacatero, Año 6, Número 32, Mayo de 2003.