Back to > Major Fruits | Minor Fruits | Underutilized Fruits

![]()

|

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

Harvesting:

Harvest Maturity Indices:

Watermelons should be harvested at full maturity to ensure that good quality fruit are delivered to the market. The fruit do not develop internal color or increase in sugar content after being removed from the vine. Harvesting usually begins 3-4 months after planting. Maturity is sometimes difficult to determine.

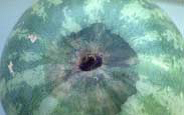

Commonly used non-destructive maturity indicators include fruit size, skin color, the amount of surface shine or waxiness, the color of the ground spot, the sound of the fruit when tapped, and the condition of the tendril at the first node above the fruit. Growers should also become familiar with the changes in external appearance of the fruit of the particular cultivar grown as it nears maturity in order to develop more confidence in the best stage for harvesting. Each cultivar has a known average fruit size, controlled by the genetic make-up of the cultivar and influenced by environmental conditions. Based on previously established average fruit size, the timing of harvest can be approximated. As the fruit approaches maturity the surface may become a bit irregular and dull rather than glossy. The ground spot (the portion of the melon resting on the soil) changes from pale white to a creamy yellow at the proper harvest maturity.

The ground spot color is easily revealed by gently rolling the fruit over to one side while still attached to the vine. Very experienced grower can determine ripeness stage based on the sound produced when the fruit is thumped or tapped with the knuckles. Immature fruit will give off a metallic ringing sound whereas mature fruit will sound dull or hollow. Another reliable indicator of fruit ripeness is the condition of the tendril (small curly appendage attached to the fruit stem slightly above the fruit). As the fruit become mature, the tendril will wilt and change from a healthy green color to a partially desiccated brown color. Several destructive indices can be used on randomly selected fruit to predict harvest maturity of the remaining fruit in the field of similar size. When the fruit is cut in half longitudinally, the entire flesh should be well-colored and uniform red (unless it is a yellow-flesh type). Immature melons have pink flesh, mature melons have red to dark red flesh, and over-mature fruit have reddish-orange flesh. For seeded cultivars, maturity is reached when the gelatinous covering around the seed is no longer apparent and the seed coat is hard and either black or brown in color. Melon fruit that has plenty of white seeds is not mature. The soluble solids content of the juice is another commonly used harvesting index. Soluble solids in watermelon consist mostly of sugars. Soluble solids content in the center of the fruit is at least 10% as an indicator of proper maturity. Soluble solids content is determined by squeezing a few drops of juice on a hand-held refractometer. In addition, the flesh of mature fruit should be firm, crisp, and free of hollow heart.

The watermelon stem should be cut rather than pulled from the vine to avoid damage to the stem end. Do not stack fruit on their ends, as this is where the rind is thinnest.

Useful maturity indicators are listed below, however it is still advisable to cut open a few fruit to check maturity before harvesting commences.

Maturity indicators include:

- A dull hollow sound when the fruit is tapped with the knuckles

- The change from white to cream or pale yellow of the skin area where the melon has been resting on the soil

- Shrivelling of tendrils on nodes to which melons are attached.

- Slight ribbing on surface of fruit can indicate maturity in some varieties.

- The Brix test is the most objective way of testing maturity. It assesses the total soluble solids (soluble solids is related to sugar content and is an indicator of sweetness) of the melon flesh. The test is becoming more popular with many retailers insisting on specific brix levels particularly in seedless lines.

A sharp knife should be used to cut melons from the vines; melons pulled from the vine may crack open. Harvested fruit are windrowed to nearby roadways, often located 10 beds apart. A pitching crew follows the cutters and pitches the melons from hand to hand, then loads them in trucks to be transported to a shed. Melons should never be stacked on the blossom end, as excessive breakage may occur.

Loss of foliage covering the melons can increase sunburn. Exposed melons should be covered with vines, straw, or excelsior as they start to mature to prevent sunburn. Each time the field is harvested, the exposed melons must be re-covered. Most fields are picked at least twice. Some fields may be harvested a third or fourth time, depending upon field condition and market prices.

International Harvest Standard for watermelon

Postharvest Handling and Packaging:

Physiological Changes:

Sugar content does not change after harvest, but flavor may be improved due to loss in acidity of slightly immature melons. Fruit can get over-ripe fairly quickly if not cooled. However, watermelon color will continue to improve for up to 7 days after harvesting if kept at temperatures of 18°-22 °C , but it will actually fade (get lighter) if kept at temperatures of below 12 °C for long periods of time. It is important to note that once harvested the sugar content or sweetness will not improve. Chilling injury will occur after several days below 5°C. The resulting pits in the rind will be invaded by decay-causing organisms. Moisture content and pH of the injured watermelon were higher than those of normal watermelon. However, color tone (Lab), hardness, soluble solid, and total amino acid and sugar contents of the injured fruit were lower than those of normal fruit.

Watermelons exposed to various concentrations of ethylene (C2H4) for 3 or 7 days of storage at 18oC deteriorated rapidly. Exposure to C2H4 reduced the rind thickness and firmness of melons. Almost all of the melons exposed to 30 or 60 µl/liter ethylene for 7 days were unacceptable for consumption.

Less than 50 % of the melons exposed to any concentration of ethylene were acceptable for consumption.

Watermelons, particularly early in the season, are sometimes shipped in mixed loads with other produce or they may be stored in central warehouses near products that may emit C2H4.Watermelons are usually harvested at their peak maturity and flavor, generally will not improve with storage. An increase in C2H4 production is associated with the respiratory peak and with the end of senescence after harvest.

Watermelons are detrimentally affected by ethylene and should not be held with cantaloupes, honeydews or other mixed melons. The whole fruit may become spongy and the internal pulp may become mealy and breakdown if exposed to low concentrations (>0.5 ppm) of ethylene.

Principal Postharvest Diseases: Postharvest diseases are important sources of postharvest loss in watermelon production. This loss depends on cultural practices adopted during production and also the local climatic conditions at harvest. Disease pressure is greater in areas with high rainfall and humidity during production and harvest. A number of pathogens may cause postharvest decay of watermelon. The primary defense against the occurrence of decay is the exclusion of diseased fruit from the marketing chain through careful selection at harvest and appropriate fruit grading before shipment. Holding fruits at 10°C will slow down the rate of disease development, compared to ambient temperature storage. There are no postharvest fungicide treatments for watermelon. Common fungal diseases that cause rind decay after harvest include black rot (Didymella sp.), anthracnose (,Colletotrichum sp.), Phytophthora (Phytophthora sp.) fruit rot, Fusarium, and stem-end rot (Lasiodiplodia theobromae). The most common postharvest bacterial disease is soft rot.

Anthracnose decay of watermelon fruit |

Greasy spot and associated whitish mold growth of Phytophthora infected fruit. |

Fusarium rot on ‘Sugar Baby’ watermelon |

Symptoms of stem-end rot |

Postharvest Treatments:

Types of Packaging:

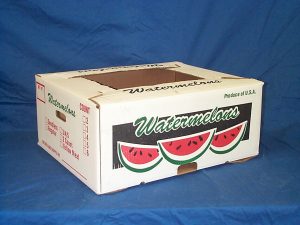

Melons should be packed in clearly marked cardboard bins. Inspect all containers to ensure no sharp objects, which may damage the fruit, are present. Ensure minimum handling of melons, as extra handling is expensive and may harm the fruit. Seeded melons are sorted and packed in large, sturdy, tri-wall fiberboard containers. The melons are sorted according to grade: number 6.4 to 11.8 kg, and number 3.6 to 6.4 kg. Inferior melons may be sold at nearby markets; culls (discolored, misshapen, sugar-cracked, rotted blossom end, and insect-damaged fruit) are discarded. Containers that hold 60 to 80 melons and weigh 500 to 545 kg are shipped on flatbed trucks to terminal markets or wholesale receivers. The containers are covered to prevent sunburn in transit.

Seedless melons are sorted according to size and packed in cartons containing 3, 4, 5, 6, or 8 fruit. “Fours” and “fives” are preferred sizes; “sixes” and “eights” are common later in the season after the crown-set melons have been removed from the vine. The rough gross weight of a carton is 18 to 22.7 kg. Seedless melons may also be sold in large bulk containers.Personal seedless watermelons are sorted by size and packed in single-layer boxes containing 6, 8, 9, or 11 fruit. Shipping boxes roughly weigh 15 kg and arranged 50 boxes per

pallet.

Storage and Transportation:

Watermelons do not store well as they are susceptible to chilling injury, and are subject to decay at higher temperatures. Watermelons may lose crispness and color in prolonged storage. Temperatures below 10 °C can result in chilling injury to the fruit (pitting of the skin, flesh breakdown and black rot). Watermelon should be cooled to between 12-15 °C within 24 hours of harvesting, if they are to be stored for long periods of time. They should be held at 10° to 15°C and 90 percent relative humidity. Under the ideal conditions of 7 ° C and a relative humidity of 80 to 90 per cent melons can be stored for up to two weeks. The general consensus is that watermelons will keep for 2-3 weeks if stored at between 12° – 15 °C.

Processed Products

Types of Products:

Processing Techniques:

Kids Watermelon Sandwich Cookies

Kids will love them!

Ingredients

12 (3-inch) blueberry pancakes, cooled to room temperature

1/2 cup white frosting

6 (2/3-inch thick and 3-inch round) seedless watermelon slices, drained to remove excess moisture

Instructions

Evenly frost the bottoms of each pancake with the white frosting. Arrange six of the pancakes, frosting side up on a serving platter. Place a slice of watermelon on each of the frosted pancakes on the platter. Top each with the remaining pancakes, frosting side down. Serve immediately or cover and refrigerate until ready to serve. Serves 6.

Watermelon Banana Split

A Healthy Twist to an Old Favorite

Ingredients

2 bananas

1 medium watermelon

1 cup fresh blueberries

1 cup diced fresh pineapple

1 cup sliced fresh strawberries

1/4 cup caramel fruit dip

1/4 cup honey roasted almonds

Instructions

Peel bananas and cut in half lengthwise then cut each piece in half. For each serving, lay 2 banana pieces against sides of shallow dish. Using an ice cream scooper, place three watermelon “scoops” in between each banana in each dish. Remove seeds if necessary. Top each watermelon “scoop” with a different fruit topping. Drizzle caramel fruit dip over all. Sprinkle with almonds. Makes 4 servings.

Watermelon Dippers

This Fresh Dip with a Hint of Sweetness Makes a Treat Kids Will Love

Ingredients

8 ounces sour cream

4 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

Watermelon stix or small wedges

Instructions

Blend together the sour cream, sugar and vanilla in a small serving bowl. Use as a dip for the watermelon.

Packaging of Products:

| Variety | Seedless Red |

| Packing | 10Kg – 12 Kg/Box |

| Count | 2/Box |

| Size | 5Kg – 6Kg |

| Storage Temp | 10°C – 12°C |

| Shelf Life | 2 – 3 Weeks |

| Carton Size | 450mm x 255mm x 245mm |

| Air Sipment | 60 Cartons / LD1 / LD3 |

| Sea Shipment | 20’RF (1250 Cartons), 40’RF (2500 Cartons) |

Types of packaging:

Reference:

- “An African Native of World Popularity.” Texas A&M University Aggie Horticulture website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Anioleka Seeds USA. “Yellow Crimson Watermelon”. http://www.vegetableseed.net/heirloom-vegetable-seeds/melon-seeds/watermelon-seeds/yellow.html. Retrieved on 2007-08-07.

- Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. “Watermelon Heirloom Seeds”. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. “Carolina Cross Watermelon”. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon/Carolina-Cross. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- (BBC) Square fruit stuns Japanese shoppers BBC News Friday, 15 June, 2001, 10:54 GMT 11:54 UK

- “Black Japanese watermelon sold at record price“. http://ap.google.com/article/ALeqM5jJBRT0pnOdQVMUzzkKC_cGHo7IdQD914F62O0. Retrieved on 2008-06-10.

- Blomberg, Marina (June 10, 2004). “In Season: Savory Summer Fruits.” The Gainesville Sun. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- “Charles Fredric Andrus: Watermelon Breeder.” Cucurbit Breeding Horticultural Science. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Collins JK, Wu G, Perkins-Veazie P, Spears K, Claypool PL, Baker RA, Clevidence BA. (2007). Watermelon consumption increases arginine plasma concentrations in adults. Nutrition 23(3):261-6.

- “Cream of Saskatchewan Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=778. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- “Crop Production: Icebox Watermelons.” Washington State University Vancouver Research and Extension Unit website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Domestication of Plants in the Old World, third edition (Oxford: University Press, 2000), p. 193.

- Dayer, R.D. (1975). The Genera of Southern African floweringbplants Vol. 1. Dicotyledons, Department of Agricultural Technical Services. South Africa: Botanical Research Institute.

- Evans, Lynette (2005-07-15). “Moon & Stars watermelon (Citrullus lanatus):Seed-spittin’ melons makin’ a comeback”. http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/chronicle/archive/2005/07/16/HOG4UDNGDB1.DTL. Retrieved on 2007-07-06.

- Hamish, Robertson. “Citrullus lanatus (Watermelon, Tsamma).” Museums Online South Africa. Retrieved Mar. 15, 2005.

- H. Mandel, N. Levy, S. Izkovitch, S. H. Korman (2005). “Elevated plasma citrulline and arginine due to consumption of Citrullus vulgaris (watermelon)”. Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft 28 (4): 467–472. doi:10.1007/s10545-005-0467-1.

- “The column of watermelon peel from 5hpk.com”.

- http://www.5hpk.com/Html/TOPIC/200807172.html. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- http://www.agriculture.gov.gy/Farmers%20Manual/PDF/Watermelon.pdf. Retrieved on 2009-07-30

- Jian L, Lee AH, Binns CW. Tea and lycopene protect against prostate cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2007;16 Suppl 1:453-7. 2007. PMID:17392149.

- Lucotti P, Setola E, Monti LD, Galluccio E, Costa S, Sandoli EP, Fermo I, Rabaiotti G,Gatti R, Piatti P. (2006). Beneficial effects of a long-term oral L-arginine treatment added to a hypocaloric diet and exercise training program in obese, insulin-resistant type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab:291(5):E906-12.

- Matos HR, Di Mascio P, Medeiros MH. Protective effect of lycopene on lipid peroxidation and oxidative DNA damage in cell culture. Arch Biochem Biophys 2000 Nov 1;383(1):56-9 2000.

- “Melitopolski Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=267. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- “Moon and Stars Watermelon Heirloom“. http://rareseeds.com/seeds/Watermelon/Moon-and-Stars. Retrieved on 2008-07-15.

- “Moon and Stars Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=266. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- Motes, J.E.; Damicone, John; Roberts, Warren; Duthie, Jim; Edelson, Jonathan. “Watermelon Production.” Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

- Müller T, Ulrich M, Ongania KH, Kräutler B. (2007). Colorless tetrapyrrolic chlorophyll catabolites found in ripening fruit are effective antioxidants. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46(45):8699-702.

- National Research Council (2008-01-25). “Watermelon”. Lost Crops of Africa: Volume III: Fruits. Lost Crops of Africa. 3. National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-10596-5. http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=11879&page=165. Retrieved on 2008-07-17.

- “Oklahoma Declares Watermelon Its State Vegetable“. 2007-04-18. http://cbs4denver.com/watercooler/watercooler_story_108064706.html. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- “Orangeglo Watermelon“. http://www.seedsavers.org/prodinfo.asp?number=1108. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- Parsons, Jerry, Ph.D. (June 5, 2002). “Gardening Column: Watermelons.” Texas Cooperative Extension of the Texas A&M University System. Jul. 17, 2005.

- Salleh, H. (1986). Constrain and challenges in melon breeding in Peninsular Malaysia. Proc. Of the Plant and Animal Breeding Workshop, Serdang: MARDI

- Shosteck, Robert (1974). Flowers and Plants: An International Lexicon with Biographical Notes. Quadrangle/The New York Times Book Co.: New York.

- Southern U.S. Cuisine: Judy’s Pickled Watermelon Rind

- http://home.howstuffworks.com/watermelon3.htm

- Stone, B.C. (1970). The flora of Guam. Micronesic 6: 562.

- Vegetable Research & Extension Center – Icebox Watermelons”. http://agsyst.wsu.edu/Watermelon.html. Retrieved on 2008-08-02.

- Wada, M. (1930). “Über Citrullin, eine neue Aminosäure im Presssaft der 28. Wassermelone, Citrullus vulgaris Schrad.”. Biochem. Zeit. 224: 420.

- “Watermelon.” The George Mateljan Foundation for The World’s Healthiest Foods. Retrieved Jul. 28, 2005.

- “Watermelon History.” National Watermelon Promotion Board website. Retrieved Jul. 17, 2005.

thank you for the recipe