China’s love of a pungent, football-sized thorny fruit is skyrocketing, and Malaysia wants a piece of it.

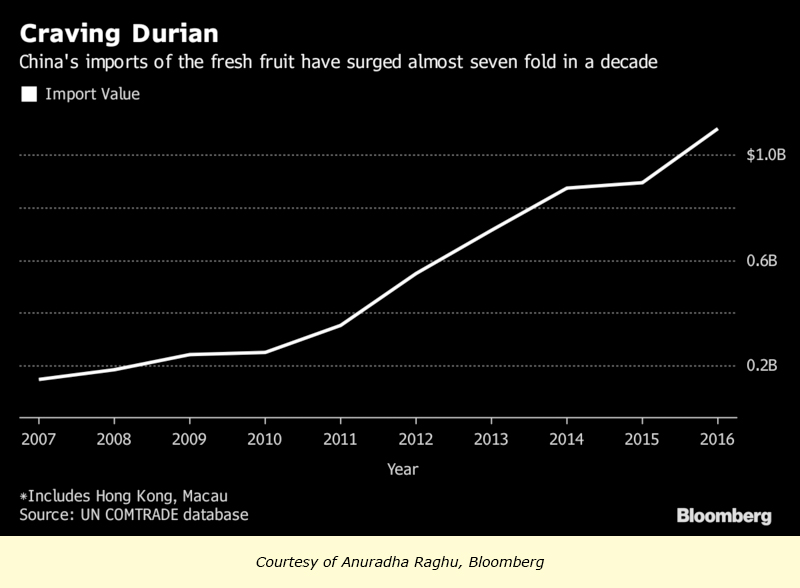

The value of China’s fresh imports of durian fruit has climbed an average of 26 percent a year over the past decade, reaching $1.1 billion in 2016, according to United Nations data. Thailand dominates that market, but Malaysian politicians are counting on durian diplomacy to expand access beyond frozen fruit pulp. A Malaysian durian festival in Nanning, in southern China, earlier this month had about 165,000 people lining up to taste thawed, whole-fruit samples of the country’s premium Musang King variety.

“Some of them said that, now in China, there are two things that people will queue up for: the iPhone X, and Malaysian durians,” Minister of Agriculture and Agro-based Industry Ahmad Shabery Cheek said Saturday. He was speaking at a durian festival in Pahang, Peninsular Malaysia’s largest state, that drew durian devotees from as far away as central China.

‘King of Fruits’

Across Malaysia, where the durian is dubbed the “King of Fruits,” orchards are recording a spike in Chinese tourists eager to savor a food that is routinely banned from hotels, airports and on public transportation for its polarizing smell.

The durian often invokes a love or hate relationship: aficionados describe the internal yellow carpels as a rich, butter-like custard, with hints of chives, powdered sugar, and caramel in whipped cream. Others are repulsed by its smell, which has been likened to rotten onions, turpentine and dirty gym socks.

In China, consumers are embracing different foods incorporating the tropical fruit, said Loris Li, a food and drink analyst with market researcher Mintel Group Ltd. in Shanghai. Durian is being used to flavor products from yogurt and cookies to coffee and pizza.

Internet Durians

Durians and durian-based products are the among the most-searched for items in China on e-commerce site Alibaba.com, said Ahmad Maslan, Malaysia’s deputy minister for international trade and industry, this month.

Malaysia’s 45,500 durian farmers are currently locked out of the Chinese market for whole, fresh durians and instead rely on exports of the pulp. That’s because they typically wait for the fruit to ripen and drop to the ground rather than climb up a tree to collect it.

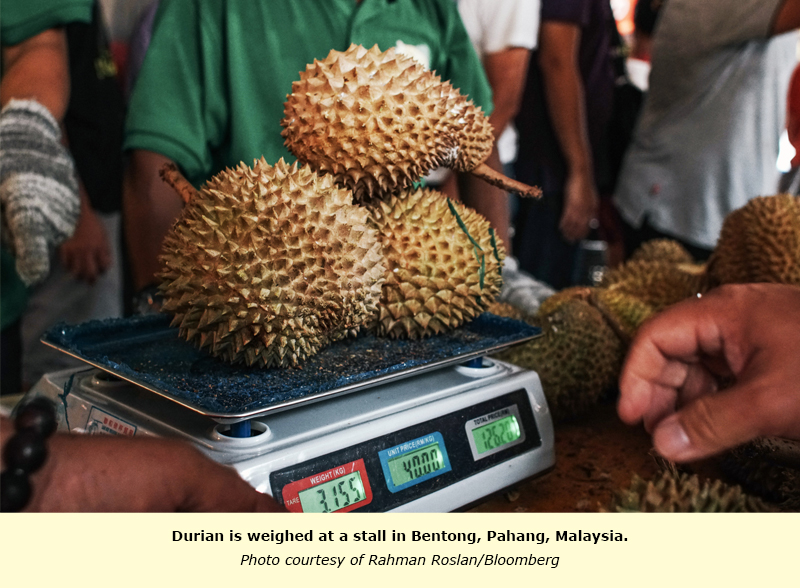

The risk of dirt and pests on the whole fruit is deterring China from accepting Malaysian product, but negotiations with the Chinese authorities may lead to approval for whole-fruit exports within a year, Agriculture Minister Ahmad Shabery told the Malaysia International Durian Cultural Tourism Festival. The ministry is working with farmers to use nets and ropes to catch the 4-pound fruit before they hit the ground, he said.

Different Taste

“We really hope that soon the whole fruit will be available in China,” said 35-year-old Churan Qiang, who traveled from Xi’an in Shaanxi province to attend the two-day event in Bentong, Pahang, the country’s top durian-growing state. “There’s a lot of Thai durians in China, but the taste is totally different from the Malaysian durian, like Musang King.”

A durian usually has about five pieces, or carpels, of yellow flesh. In China, a single piece may cost about 100 yuan ($15), said Qiang, who planned to bring home about 5,000 yuan worth of Malaysian product.

She represents the kind of tourist Transport Minister Liow Tiong Lai wants to lure to Bentong. The government plans to develop the rural town into a durian tourism center, Liow told a cheering crowd at last weekend’s festival.

Price Surge

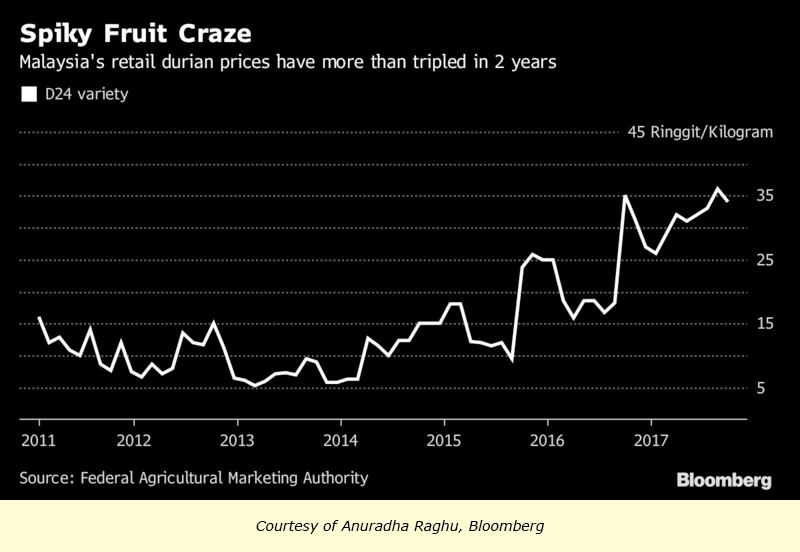

It’s fine if durian prices increase because of Chinese demand — as long as farmers benefit and the economy grows, he said to a muted crowd. Enthusiasts don’t like expensive durians, and prices have escalated in recent years.

As some Chinese durian-lovers search for the best all-you-can-eat buffets, others are hunting for orchards to cut out the middle man.

Owning a durian farm in Malaysia is not only a profitable investment, but also a sign of prestige, said Jayson Tee, an agriculture land agent in Pahang. Buyers from China are motivated by the prospect of inviting friends and family to their farms for durian feasts.

Investment Opportunity

“The price of durians keeps going up, so this is their investment opportunity,” Tee said. “And of course, they love durians.”

Depending on location and accessibility, a farm with 6-year-old trees goes for about 400,000 ringgit per hectare (USD 40,000 an acre), while those with mature, 10-to-12-year-old trees command at least double that, said real-estate agent Eric Lau.

Growing durians can be a lucrative business. Orchards can return about 100,000 ringgit (USD 10,000) a hectare annually, compared with 30,000-to-40,000 ringgit (USD 3,000-4,000) for a hectare of oil palm, the country’s major crop, Ahmad Shabery said.

Still, the business can be frustrating as “durians are the most challenging” fruit to grow, according to Teo Chor Boo, an agronomist with Applied Agricultural Resources Sdn, which advises farmers on crop management. The fruit development process is fragile, and trees are susceptible to disease, and sensitive to changes in soil moisture and nutrients, he said.

Curbing Tourists

Eddie Yong, who keeps about 400 mostly Musang King trees, is finding he’s almost too good at growing the fruit. His orchard in Raub, Pahang, about 107 kilometers (68 miles) east of Kuala Lumpur and 460 kilometers north of Singapore, is having to limit the number of tourists to 150 a day after an increase in visitors from Hong Kong and China.

Durians from estates in Raub are highly sought after for their creaminess and bittersweet flavor that stems from the area’s soil and terrain, said Yong, 57, who began the orchard more than 30 years ago.

“People travel all the way from Singapore just to taste the durian,” he said. “They come early in the morning and then drive back the same day.”

Yong recently turned down a 5 million ringgit offer from a Chinese investor for his 4-hectare farm, he said. “They offered me a good a price, but I don’t want to sell,” Yong said. “This is my life, my passion.”

Written by Anuradha Raghu, Bloomberg

Source: Bloomberg