A week ago chef Eric Leterc at The Pacific Club in Honolulu put up a sign apologizing to customers.

Due to volcanic activity on the Big Island, the club’s kitchen was experiencing a shortage of papaya.

“We are uncertain at this time when stock will be replenished as Madame Pele continues to exhibit her strength,” the sign said. “We appreciate your understanding and look forward to serving you.”

Leterc said he typically orders local papaya daily, which is popular for breakfast as well as on the lunch menu for his featured chicken salad served in a papaya. If the shortage continues, he will have to substitute with pineapple.

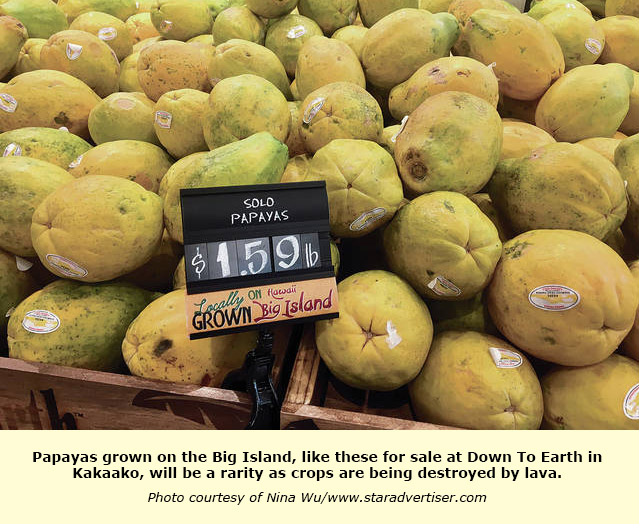

As lava continues to fountain and flow into the ocean since eruptions in Leilani Estates began May 3, the destruction of many papaya-producing farms in the lava’s pathway is already being felt throughout the state, from distributors to chefs and customers. The situation is even more devastating for papaya farmers who have lost both their homes and livelihoods.

The local papaya shortage is expected to be felt now as well as in the future, according to Eric Weinert, president of the Hawaii Papaya Industry Association.

Weinert estimated at least 90 percent of papaya in Hawaii is grown in Puna.

“The reason for that is the best papaya in the world is on lava lands, because it’s well drained,” Weinert said. “It gets rainfall but it’s well drained. That’s why Hawaii papaya tastes better, because of those soils.”

The triangle delineated by Highways 130, 132 and 137 in Puna, more than 2,000 acres, represent up to half of the papaya lands in the area, and all of it is either buried by lava or inaccessible, he said. Even if not covered by lava, the sulfuric oxide gases have destroyed papaya trees. At least 150 farmers have been affected.

“I just confirmed with a farmer, almost 40 acres of papaya,” he said. “The gases burned the tops of all his papaya trees.”

Besides the loss to farmers and their families, the impact includes the loss of jobs and exports.

Approximately half of the papaya grown in Hawaii is consumed here, and half is exported to the mainland, Canada and Japan, said Weinert, also general manager of Calavo Growers.

Papaya grows on a three-year rotation, he said, so recovery from the shortage won’t be immediate.

“It affects everything going forward,” he said.

Based on the latest statistics available from the National Agricultural Statistics Service, there were 1,300 acres in papaya production on the Big Island in 2016. There is no breakdown based on district.

At Armstrong Produce, a produce wholesaler and distributor, marketing director Tish Uyehara said shipments have dropped by more than half. Whereas Armstrong used to receive 1,200 to 1,400 cases of papayas per week from the Big Island, it is now getting only 480 to 500 cases per week.

While Armstrong also receives papaya from Oahu and Molokai, it is not nearly as much as the quantity that comes from the Big Island.

“For us it’s what are we going to do without papayas,” she said. “It’s something people look forward to eating when they come to Hawaii. At the same time, this is Mother Nature at play.”

Gareth Mendonsa, a state agricultural loan officer, said he has been assisting farmers from Opihikao to Kapoho. Besides orchid farms, a tropical plant nursery and macadamia nut farmers have also been affected. Many of the papaya growers in Puna are independent and have decades of experience. Some are second-generation farmers.

The state Board of Agriculture approved an emergency loan program, offering disaster-related loans of up to $500,000 at an interest rate of 3 percent to farmers suffering from damage due to the Kilauea eruption.

Mendonsa said the loans are available for operating expenses and startup costs, from acquiring land to clearing the field up to harvest. However, the challenges for papaya farmers include relocating and securing a lease to plant a new crop. Ideal lands for growing papaya are difficult to find, he said. Loan applications will be accepted through June 2019.

“Right now they’re scrambling,” he said. “We’re trying to assist them the best we can.”

Weinert said the loss of papaya production in Puna is a devastating blow for the economy, with many farms supporting several families. He said he hopes the government will work with the private industry to help farmers who have proved themselves to be productive over the years.

“To bring these people back,” he said, “we’re going to have to come up with some land, figure out how to get these people capital and have some incentives.”

Source: Nina Wu, Honolulu Star Adviser