What is the point of sticking to paddy when mango is more profitable and easier to farm? What is the point of living in uncertainty and poverty?

This is what Saday Chandra Debnath thought before he quit paddy farming.

The 28-year-old farmer of Naogaon’s Sapahar upazila was facing an overwhelming debt burden due to frequent losses caused by low paddy prices. Adding to his misery was the constant worry about where to find the irrigation water if it does not rain.

“We can’t get profit from paddy. The price remains low in most seasons,” Saday said, talking to The Daily Star. “Irrigation water is scarce in our area, so we have to depend on rainfall. This is a permanent concern.”

Two years ago, he did away with paddy farming and leased his land out to a mango grower who turned the fields into a commercial mango orchard.

Saday now earns more than he used to do from paddy cultivation.

He owns eight bighas of land. From each bigha, he would earn barely Tk 7,000 (USD 83) from paddy farming, which was lower than the production cost of Tk 8,000 (USD 95).

Now he gets Tk 12,000 (USD 143) annually for one bigha as the lease money, without having to spend a penny. In addition, he supervises the orchard for a monthly pay of Tk 9,000 (USD 107).

“A confirmed income comes without worry,” Saday told The Daily Star.

Saday was one of the many farmers in Rajshahi region who are leaving paddy farming due to scarcity of irrigation water and recurring losses.

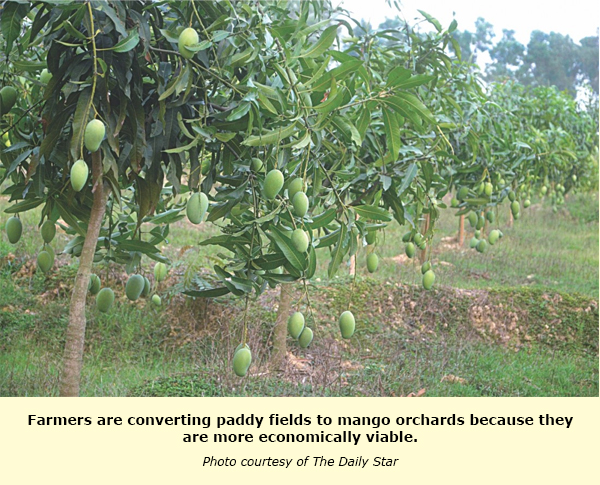

The farmers are either leasing their land out to mango growers or cultivating the fruit themselves, according to agriculturists and farmers.

Paddy cultivation is the “most uncertain” among crops in some areas of high Barind region where rainfall is low and irrigation water is difficult to get, said Deb Dulal Dhali, additional director of Department of Agricultural Extension (DAE).

“Only because of the water crisis, many farmers are switching to fruit cultivation.”

The officer said that for being a highland, it is difficult to install deep tube-wells there. “So, rainwater becomes their only source of irrigation water.”

Md Moniruzzaman, agriculture extension officer in Sapahar upazila, said, “If the farmers see a fall in paddy prices in a given year, the number of mango orchards goes up the next year.”

This was the trend in the last nine years from 2008-09 to 2017-18. In this period, the paddy cultivation area has shrunk by 2 lakh hectares in the region covering four districts — Rajshahi, Chapainawabganj, Naogaon and Natore. At the same time, the amount of land covering mango orchards doubled to 70,346 hectares.

Every year new mango orchards, especially of Amrapali, BARI mango-3 and 4 varieties, are rapidly increasing in the districts, said agriculturists.

Naogaon was long known for paddy cultivation, but last year it became the highest mango-producing district, surpassing the mango capital of Chapainawabganj.

Chapainawabganj still has the highest amount of land covered by mango orchards, but Naogaon saw a one-and-a-half-times increase in its mango farm acreage annually over the last 10 years, according to DAE data.

The area covered by mango orchards in Naogaon increased by 14,925 hectares in the period; while the increase was 9,520 hectares in Chapainawabganj.

In terms of production in 2017-18, Naogaon tops the list with 315,607 tonnes. It was followed by Chapainawabganj (275,000 tonnes), Rajshahi (213,426 tonnes), and Natore (62,328 tonnes).

MANGO FARMING METHOD CHANGING

Mango farming is not only increasing, but it is changing as well. Instead of creating mango orchards for a hundred years or more, farmers are targeting only 10 years.

Normally 10 mango trees are planted in one bigha of land, but in the new farming method, farmers can plant up to 200 trees in the same space, said Md Nuruzzaman, a mango grower of Porsha upazila of Naogaon.

“These trees will bear fruit for 10 years or less, and then we have to uproot them and replant.”

The growth of mango orchards is the highest in two Naogaon upazilas — Porsha and Sapahar. They have 72 percent of the orchards of the district, says DAE.

In a recent visit, this correspondent saw most mango orchards in the two upazilas were new and bearing fruits.

Nuruzzaman began mango farming in 2001 after completing his madrasa education.

“I learned about the Indian mango variety, Amrapali, when I was studying in a madarasa in the border area of Hili,” he said.

“Instead of looking for a job, I decided to cultivate eight bighas of land I inherited.”

He said, “Paddy cultivation was never profitable in our area. I have an uncle, Mojadded Hossain. He is an agriculturist. He inspired me towards mango farming.”

Nuruzzaman collected seven Amrapali saplings from India for Tk 120 (USD 1.42) each and planted those in his land. After three years, he began expanding his mango farm, taking lease of land from other farmers.

Now he cultivates mango on 70 bighas of land, quality varieties (Khissapat or Himsagar, Langra, and Fajli) on 15 bighas and Amrapali on 55 bighas.

Nuruzzaman said he makes a profit of Tk 20,000 (USD 237) every season from each bigha, while the cost per bigha is Tk 10,000 (USD 119). “I earn enough for my family, and I gave jobs to many villagers at my orchards.”

Unlike Nuruzzaman, Saifuddin Mondol of Sapahar was relatively new in mango farming.

He used to cultivate paddy on 20 bighas of land two years ago when he decided to bring paddy acreage down to seven bighas.

Saifuddin turned the remaining 13 bighas into mango orchards. Later he took lease of 50 bighas land from farmers paying them Tk 12,000 (USD 143) per bigha annually.

“In mango farming, the possibility of loss is low,” he said.

Source: Anwar Ali, The Daily Star