Chinese consumers have embraced the craze for the fruit only in recent years, but that is making life ever more difficult in one of its source countries, the programme China’s Growing Appetite finds out.

It is a superfood, packed with vitamins, minerals and fibre. And in China, avocado has also become a social media superstar since a fitness craze took the country by storm about six years ago.

More and more people are working out, toning up and showing off on social media, including what they eat to help burn fat and gain muscles.

In Shanghai, one avocado restaurant is taking to social media at a whole new level, with its marketing done entirely through word of mouth online.

Kiss Avocado even has a pink decor to attract girls who would “take selfies and post on social media”, said co-owner Lynn Yin. And as the Chinese middle class grows, more of them are eating such trendy foods.

A decade ago, China’s volume of avocado imports was low: 31.8 tonnes in 2011. But it has increased by more than 1,300 times, to 43,000 tonnes in 2018.

Previously, an avocado from Mexico retailed domestically at about 50 yuan (S$10), in no small measure because of a 40 per cent total tax rate for the fruit.

But in 2014, Beijing granted market access to Chile. And under a bilateral free trade agreement, Chilean avocados have since entered with zero tariffs. By 2017, half of China’s avocados came from the South American country.

The fruit now costs about 10 to 15 yuan, whereas in Chile, the price has tripled to 3,200 pesos (S$6) per kilogramme, observed FoodyChile tour guide Colin Bennett.

“When I first moved here (12 years ago), it was 1,000 pesos a kilo,” said the American, who settled in Santiago, the capital.

The amount of water it takes to produce one avocado is enough to grow three oranges or 14 tomatoes. And plantations have been extracting “more water than authorised”, said Mundaca, who is fighting to protect local communities’ access to water.

A 2011 investigation by Chile’s water authority showed at least 65 illegal underground channels bringing water from the rivers to private plantations.

The investigation led to criminal convictions of some agribusinesses, but that was not enough to stop them from trying again.

They still dug riverside wells to irrigate their fields, Mundaca pointed out at one such site that was fenced off to keep it out of sight.

“This is a river. It’s a national good for public use,” he said. “You can’t simply install underground water (systems). This is fully illegal.”

One of the province’s rivers, the Ligua River, was declared depleted as far back as 2004 — “overexploited” by avocado producers, he added.

In the past 10 years, however, central Chile has also been living with a mega-drought. So nearly half of the country’s rural homes — some one million people — do not have regular access to drinking water nowadays.

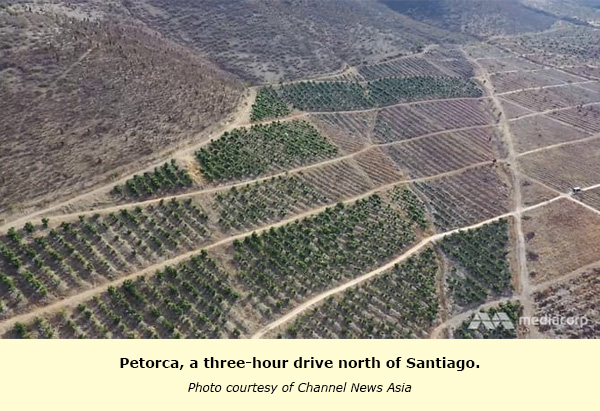

As the groundwater level continues to drop, the local government has resorted to trucking water to Petorca’s rural residents. They are among 380,000 people in Chile receiving water from tankers as part of emergency measures declared last year.

Asked if the plantations can be stopped from drawing too much water, Petorca municipal government’s water affairs manager Carolina Vilches replied that the municipality “doesn’t have the power to evaluate the environmental impact of agriculture”.

“The ministry that has that power doesn’t consider agriculture as something that could impact the environment. Therefore the impact isn’t assessed,” she said.

VILLAGERS VS FARMS

It is obvious, however, that families are struggling with the lack of water. “(The most difficult thing) is seeing how everything dies — it’s terrible to see our little plants die — (and) washing up with so little water,” said Zoila Quiroz.

Her family, who have lived in the Petorca valley for generations, used to get water from a stream four kilometres away. But it dried up, and they do not own rights to dig a well to get water.

That is not the case for the avocado farms surrounding the family on all sides. “The avocado trees have more rights than us, the human beings,” added Quiroz, wishing that the farms could all go.

“I think this is the only part of the world where water is sold like candy.”

It turns out that in Chile, water rights are treated like property and granted in perpetuity by the government. With the drought, and plantations sometimes drawing more water than they have rights to, there are no more rights to allocate.

While villagers are losing out in this way, Allent Vega Diaz disagrees that the criticisms are fair. The farm manager from Cabilfrut, the biggest avocado exporter in Petorca, pointed out that Chilean law “doesn’t discriminate between the uses of water”.

Nor does he think the government should change the law. “The government needs to invest to secure water for the population. People without water need water; they don’t need laws,” he said.

“This area needs agriculture. Agriculture is the main activity in this area.”

Source: Channel News Asia