The sprawling citrus orchard that Victor Story toured recently sure looked like a steal. For sale at $11,000 an acre, the investors who owned it were going to lose money, and potential buyers like Story might have stood to reap a handsome reward.

The sprawling citrus orchard that Victor Story toured recently sure looked like a steal. For sale at $11,000 an acre, the investors who owned it were going to lose money, and potential buyers like Story might have stood to reap a handsome reward.

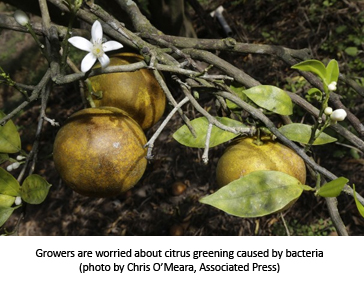

But as he bumped along the 40 acres of groves in a large SUV, Story was taken aback by the sickly look of the trees. Their leaves were an inch shorter than normal and yellowing. Full-size oranges were still apple green. Other mature oranges that should have been the size of baseballs were no bigger than ping-pong balls.

“That fruit’s never going to be of any value,” said Story, 68, who has been growing fruit all his life. He said his pickers wouldn’t even bother to reach for it. “It’s going to fall off the tree; it’s never going to get squeezed,” he said. “These investors paid $15,000 an acre for that grove. I know because they bought it from a friend. I frankly don’t think it will sell for $11,000.”

What Story saw in the orchard in Polk County, Fla., wasn’t an anomaly. It’s the new norm in the Sunshine State, where about half the trees in every citrus orchard are stricken with an incurable bacterial infection from China that goes by many names: huanglongbing, “yellow dragon disease” and “citrus greening.” Growers, agriculturalists and academics liken it to cancer. Roots become deformed. Fruits drop from limbs prematurely and rot. The trees slowly die.

The bacteria is spread by a tiny, invasive bug also from China, called Asian citrus psyllid. It acquires the bacteria while feeding on the leaves of infected trees, then transmits it when feeding on healthy trees — akin to the way mosquitoes transfer malaria.

Psyllids were first detected in a Broward County, Fla., garden in 1998 and spread to 31 other counties within two years. The Asian strain of the bacteria was discovered in 2005 just south of Miami. The disease ruins the look and taste of the fruit but isn’t known to harm humans.

Florida citrus, which provides up to 80 percent of America’s orange juice, has been hardest hit, but the disease — which also has an African and Latin American strain — also has been detected in Georgia, Louisiana, Texas, Arizona and California. It has spread to other parts of the world, including Mexico, India, sub-Saharan Africa and Brazil, which provides nearly 20 percent of the orange juice Americans drink. In each case, the impact to citrus has been devastating.

Worldwide concern prompted 500 scientists from more than 20 nations to gather in Orlando last February for a conference on huanglongbing. Despite the fact that nearly $80 million has been poured into research on the disease, scientists still don’t know how to eliminate the bacteria or remove it from trees.

Even those who are optimistic about a scientific breakthrough admit that if the infection continues unabated for another decade or so — admittedly a worse-case scenario — Florida’s $9 billion citrus industry could be destroyed.

“What’s at stake is orange juice on the breakfast table,” said Michael Sparks, chief executive of Florida Citrus Mutual, a trade association. “I don’t want to indicate that’s going to happen next year. With a 10-year decline, your supply will reduce.”

Researchers funded by the industry, the state and the U.S. Department of Agriculture are exploring an option that could save the trees and their citrus, but also turn off consumers: engineering and planting genetically modified trees that are resistant to the bacteria carried by the psyllid.

“Would that be accepted by the public?” Sparks asked. “You don’t have to do a focus group or another survey to know it is a public concern.”

He said he and the growers hope they don’t get to the point where they have to use a genetically modified plant.

The threat to the world’s citrus production is another example of how, in an era of global trade and travel, viruses, insects and animals are inadvertently transported to places they don’t belong. Pythons from Latin America and Africa are threatening the natural balance of wildlife in the Everglades; a fungus from Europe is wiping out bats along the East Coast; stink bugs from China are attacking farm crops and invading homes in the Mid-Atlantic region and the voracious Asian snakehead is devouring native fish in the Chesapeake Bay.

Even before being hit by the disease, Florida’s orange, grapefruit and specialty fruit crops faced many threats, including hurricanes, frost and a fungus that causes canker disease. The crops have been declining since the mid-1990s.

But the decline has accelerated since the detection of huanglongbing, said Harold Browning, chief operating officer of the Citrus Research and Development Foundation, a nonprofit agency that studies the disease under the guidance of the University of Florida.

Since the disease’s detection in Florida City and Homestead, 90,000 acres of citrus have been wiped out. The high cost of spraying to kill off some of the psyllids is pushing some growers to the financial brink. The average cost of producing an acre of oranges is $1,800, nearly double what it cost in 1995.

“It’s a huge amount of money,” said Stephen Futch, a University of Florida extension agent. A 2012 analysis estimated the disease has cost growers $4.6 billion and resulted in the loss of about 8,000 jobs.

In the heyday of Florida citrus, around 1970, the number of acres with orange, grapefruit and specialty fruit orchards surpassed 900,000. Today, it’s only slightly more than 500,000 acres, according to an analysis by Futch.

But consumers have felt only a subtle pinch, he said. “The (orange juice) container got smaller, not significantly, from 64 ounces to 59 ounces. That’s a way to do a price increase without raising the price.”

Growers represented by the industry trade group “believe we are at a crossroads this year,” Sparks said. Banks are watching closely to see if they can produce enough citrus to repay their debts.

“The small growers are saying: Should I continue to invest?” Sparks said. “The citrus industry is built on the backs of smaller growers. In the state of Florida, we have 135,000 acres that have been abandoned.”

Story sprays the 2,000 acres of orchards he owns under his business, Story Cos., in an attempt to kill as many psyllids as possible. He sprays an additional 3,000 acres he manages for investors who don’t farm through a side business called Story Citrus Service.

A team of six sprayers start at 10 p.m., when the winds usually die down. They try to treat 200 acres per night, spraying until 6 a.m.

“I fall asleep looking at the radar on my phone to make sure there’s no rain,” Story said. “We don’t want it to wash off.”

Even then, the spraying keeps the psyllid at bay for only 30 days, “no longer than 45,” he said.

“Four years ago, I would see an occasional tree with this disease. I can remember seeing the first grove and seeing the first tree,” Story said. “This year I can ride around and see greening symptoms on 75 percent of my trees.”

None of that matters, Story said, because he and a determined corps of medium-size growers aren’t about to give up.

“When we lose a tree, we put a tree back,” he said. “We’re constantly resetting. There are people that are committed to this industry.”