At Patco greengrocer’s on the Romford Road in east London, there has been a run on Indian mangoes. Boxes cradling a dozen yellow-orange fruits packed in straw, some oozing aromatic juices indicating peak ripeness, have been flying out of the store.

“Customers who usually buy one box a week have been taking four,” said the owner, Krunal Parikh. “I stocked 100 boxes and most are already gone.”

“Customers who usually buy one box a week have been taking four,” said the owner, Krunal Parikh. “I stocked 100 boxes and most are already gone.”

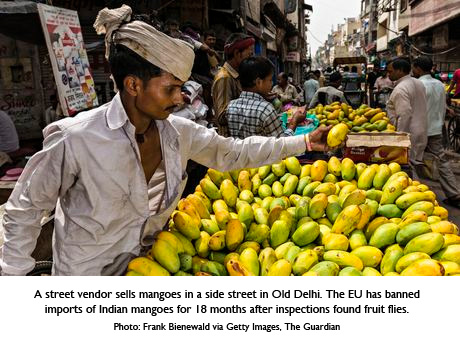

The reason is a European Union ban. Brussels has blocked imports of Indian mangoes until December 2015 after inspectors found some consignments infested with fruit flies.

The ban has left connoisseurs practically in mourning for an annual ritual that heralds the start of summer, even in Britain.

Mangoes are grown in south-east Asia, India, Pakistan, parts of Africa, South America and in the Caribbean. But many people consider the Indian varieties to be the best.

“You get wine all over the world, but there is only one region where they produce real champagne,” said Pushpesh Pant, a food anthropologist in New Delhi. “Mangoes from Mexico, Indonesia, Brazil, China, Thailand or Pakistan don’t even bear mentioning in the same breath as Indian mangoes.”

Popular Indian varieties include the small Dussehri, grown in northern India, and the big green Langra, from near the Hindu holy city of Varanasi.

But the Alphonso, so-called “king of the mangoes,” grown on India’s western coast and named after the Portuguese explorer Afonso de Albuquerque, is considered the richest in flavour and is a major export.

“The Hapuz [Alphonso in Indian languages] has a delicate fragrance, firm orange flesh, it’s not overly sweet. The juice is not too gooey and its soft yellow skin is just beautiful to look at,” said Pant, whose own personal consignment of the season’s first mangoes was shipped to him on Wednesday.

“In India, there are very few orchards that produce the best Hapuz mangoes and their crop is usually pre-booked months in advance,” he said.

Mango mania begins in mid-April when the first fruits appear, and continues into early July. Unlike strawberries grown for a longer season in greenhouses in Spain, or grapes, which can be sourced from multiple parts of the world, Alphonso mangoes remain one of the few truly seasonal fruits.

“During Indian mango season, it just goes crazy,” said Anil Mudumbi, founder of itadka.com, an Asian online grocery retailer in the UK where a box of Alphonso mangoes usually sells for £14.99, the most expensive variety on offer.

Bought mostly by an estimated 2 million British Asian customers, the mangoes are not available in major supermarkets. Rather they are sold by specialist retailers like Mudumbi.

For many British Asians, mangoes can evoke strong memories of extended family picnics in India, where mangoes stored in cold buckets of water are passionately fought over among cousins.

The Indian government has demanded the EU lifts the ban, arguing that measures have now been put in place to address its concerns.

“It’s just a few harmless fruit flies,” said one customer at Patco. “We’ve been eating them for years and we’re not sick.”

With mango stocks in Britain already running low, retailers and customers are wondering how they will cope this summer.

“Eighteen months is just too long,” said Mudumbi. “My little girl eats three mangoes after dinner most nights. I’m in two minds. If I let her gorge, how will I wean her off them when they suddenly run out?”

Some Indian farmers and exporters will also be hit hard.

“I only export to the UK, so my business has effectively collapsed,” said Desmukh Saudavadiya, who runs Shreeji Mango Farm, a 40-acre orchard in Saurashtra, Gujarat. “Normally I would export up to 250 metric tonnes in a season, but this year I’ve shipped just six tonnes.”

The ban is expected to depress prices in India, a prospect that has delighted mango lovers, including Pant, who is already relishing his next taste.

“The Indian way of eating it is to cut a hole at the top and then squeeze the pulp out,” he said. “But I like to eat it the Anglo-Indian way where you cut both sides with a sharp knife, keep the stone aside and then use a spoon to scoop out the flesh, which keeps your hands clean.”

Source: The Guardian