Last January, I visited a friend and took pictures of her mango tree that was covered with flowers. A few weeks later we talked on the phone and she told me the flowers had fallen without turning into fruit. She jokingly said that by taking pictures I had put a jinx on her tree.

When I visited the Philippines in November, 2010, I brought a mango sapling of the kind that bears big fruit and gave it to a relative, who planted it on his farm. Last week, a nephew sent me a picture of the tree. It is about 130cm tall, and has yet to bear fruit. The sapling was grafted from a mature tree, and should have started bearing flowers in its first year and fruit the following year.

When I visited the Philippines in November, 2010, I brought a mango sapling of the kind that bears big fruit and gave it to a relative, who planted it on his farm. Last week, a nephew sent me a picture of the tree. It is about 130cm tall, and has yet to bear fruit. The sapling was grafted from a mature tree, and should have started bearing flowers in its first year and fruit the following year.

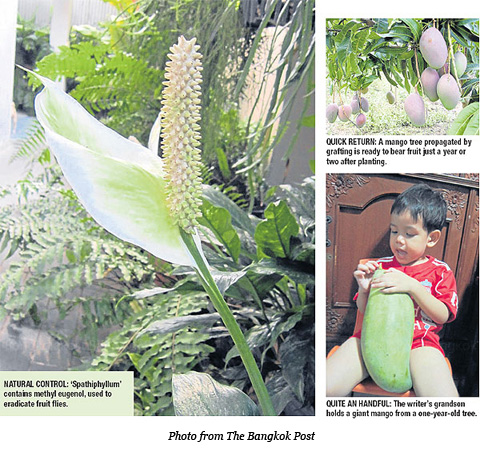

Actually, the tree can be allowed to bear fruit in its first year if it is already big enough. A few months after I gave the mango sapling to my cousin, we planted the same variety on our farm. It bore flowers when it was a little more than one year old, and gave us three huge fruits. Now more than two years old and more bushy than my cousin’s tree, this year it had 10 fruits, although we did not get to taste any as fruit flies got to them first.

Fruit trees grow faster and bear more fruit when you give them fertiliser, the amount of which depends on the size or age of the tree. In its first year, apply 500g of complete fertiliser (NPK 15-15-15), divided into three applications at the start, during and at the end of the rainy season. Alternatively, you can apply the fertiliser six months apart, before and after the rainy season. As the tree becomes bigger and older, the quantity is increased. A fully grown tree may need at least 500g per application. However, if organic fertilisers like compost and fully decomposed animal manure are used, the amount of inorganic fertiliser may be reduced.

Trees can be planted in any month of the year, but now is the best time as it is the start of the rainy season. There are three advantages to this — watering is minimised, there is no need to shade the newly planted tree from the sun and the tree’s root system has time to grow and become fully established before the dry season begins.

To plant a tree, dig a hole wide and deep enough to accommodate the tree’s root ball, and mix the soil taken from the hole with compost and animal manure. Remove the plant from its container by pushing it from the bottom and holding the root ball so that the original soil remains intact, then gently place the plant erect in the hole, fill the hole with soil, and water thoroughly.

Sometimes, when the sapling is planted in a black plastic polyethylene bag, some gardeners only make cuts on the bag to expose a few roots before planting, thinking that the bag will decompose later. However, it takes a long time before the plastic bag decomposes under the soil, so it is best to discard it before planting.

Organic material provides a healthy environment for the growth of soil organisms, such as bacteria and fungi, which transform nitrogen and other elements into usable compounds that the plants can absorb. The process, however, takes time; for fast vegetative growth, inorganic fertiliser is also necessary. Apply it one month after planting, and again after three or six months. Make sure to water thoroughly every time you fertilise, and keep the area around the base of the tree free from weeds. During the dry season, add mulch to retain moisture.

If you have established or mature trees, now is also the time to apply fertiliser. Some growers think that mature trees do not need additional food supplements, but if my friend had given her tree a fertiliser high in phosphorus and potassium, the flowers would have had more chance of turning into fruit — if they had been pollinated, that is.

To fertilise a mature tree, drill holes in a circle just inside the drip line (where the water drips if the tree is compared to an umbrella) as most of the feeder roots are around this area. The holes are to keep the fertiliser from being washed away, and need not be very deep. Make holes 50 to 60cm apart. If you are applying 500g of fertiliser, divide this by the number of the holes you are going to fill then insert the fertiliser in the holes accordingly. Water immediately and thoroughly to avoid burning the roots. This method can be applied to all kinds of fruit trees as well as ornamental trees.

Oriental fruit flies are the bane of orchard growers. Thin-skinned tropical fruits such as mango, starfruit, roseapple and guava, as well as some not-so-thin-skinned fruits such as santol, are very susceptible to fruit flies. They are often wrapped or put in plastic or paper bags while still young on the tree to keep them safe from the insects and to keep

their skin unblemished. If I lived on the farm I would have wrapped the giant mangoes so that the insects could not get at them. But I don’t, and by the time the caretaker realised there was an infestation, it was too late to save the fruit.

Researchers have found that the male fruit fly is attracted to methyl eugenol, a chemical compound extracted from the flowers of the Spathiphyllum sp, known in Thai as daylee, and a number of other plants. By using the compound, now commercially available, as a trap, the pest can be eradicated or minimised.

Young mango trees produced by grafting usually do not require any special training as their branches are close to the ground and they usually assume a satisfactory form. However, dried twigs and diseased branches should be removed, and interlacing branches and excessive growth inside the tree should be pruned to improve aeration in the interior of the tree. Pruning both young and old trees enables sunlight to get through to the inner branches, which in turn promotes fruit formation and growth.

Source: The Bangkok Post